This exercise required me to search through my own family photographic archive and try to discover a series of portraits (four or five) that have existed within the archive, but have never been placed together before. The portraits can contain individuals or even couples; they may span generations, or just be of the same person throughout the years (chronotype). Whichever way you wish to to tackle this exercise, there must be a reason or justification for your choices. What message are you trying to get across about these portraits?

My parents house contains the vast majority of our family photographs, particularly those that are more than 15 to 20 years old, in other word, our analog archive. Mobile phone technology has meant that my family, myself included, have large individual archives of photographs which remain stored in some digital form, albeit on our phones, hard-drives, cloud and/or other online store technology. The digital age has seen exponential growth in photographic capture, with the complete opposite in terms of photographic printing.

I live a considerable distance from my parents house, and so with time and distance playing a key role in my execution of this exercise, I enlisted the help of my mother and sister. Asking them to look at our family photo albums on my behalf, I simultaneously consulted my own digital archive. While viewing my own digital archive and hearing feedback from my helpers, it became clear that I needed to be very specific as to what they were to look for. Making myself the subject of the exercise was the best option available to me and my helpers. The first three photographs were sent by text message from my sister, after she rephotographed them with her phone. While the quality isn’t particularly good, it suffient for the purpose of this exercise. The last two photographs were taken digitally, one by an army friend and colleague, while the other was taken by me using my camera’s self-timer.

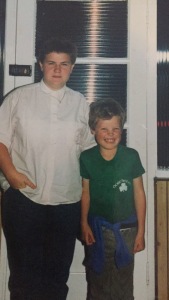

I chose the five photographs below for a number of reasons. Firstly, I’m the common denominator across the series, which is a chronotype of sorts. The series begins with me as a toddler in late 1979/early 1980 outside the backdoor of my grandparents house in County Kerry. They ran a bar and ‘ladies’ (denoting the direction to the ladies toilet) can be seen on the wall behind me. The smiley, laughing child is very much a symbol of the happy childhood I recall, and my grandparents house is a place I remember fondly. The next photograph was taken later that same year after our family moved to Lagos, Nigeria, for a period of five years. I’m held in my mother arms as we visit Santa Claus in a Lagos department store. This photograph is very different to those of my friend, and even to all subsequent Santa visits we had after returning home to Ireland. I don’t thing I know anyone who went to visit such a cool Santa Claus. Even if their Santa Claus happened to be wearing sunglasses, in Ireland in the 80’s/90’s, and sadly, even today, Santa was always going to be played by a white man. And so, the photograph marks the interesting childhood I had in Nigeria. The third photograph features me again in my grandparents house, posing with my cousin from Boston. I’m again smiling and my posture is probably tells a little of the shy awkward child that I was for a time. The next image is from 2004, while serving in the Irish Army on overseas deployment with the United Nations in Liberia. I’m proud of my time in the Army, and it is a significant period of my life. Finally is a photograph taken in March of this year (2017) while traveling in Laos with my girlfriend. Having been together for 9 years, we decided to take off and see a bit of the world together.

Overall the series of photographs portray a happy life and there are a number recurring elements or themes. I spent some of my childhood in Africa, and later returned as a peacekeeper, both of which are represented. The series is punctuated by modes of transport, the buggy/pushchair, armoured personnel carrier, motorcycle and even my mother arms, which reinforce the idea that I’m a person who has always had strong support behind me, i.e. family, the army, my partner. The over all message of the series is that of a happy, well lived and enjoyed life. The final photograph, from a journey that is now over, shows two people posing by their trusty steed, and is perhaps suggestive of the road ahead, yet to be travel.