The shoot

When photographing strangers as part of Exercise 1.3 – Portraiture Typology, I generally received far more positive responses than negative. After that shoot, as promised, I email each subject their individual photograph along with a contact sheet showing everyone who posed for me that day, which I believed would help contextualize my intention. I was energized when all those subjects responded with gratitude and encouragement. Brimming with confidence, I set out on a bright sunny day to carry out the assignment shoot. I began mid morning and spent between three and four hours calling into shops in the inner city area. I was focusing on the smaller shops that had a small staff and were generally tended by the owner. In hindsight, it seems that I may have been a little naive as I set out that morning. I called into approximately 40 shops, and the vast majority said ‘No’. At the time, the high volume of rejection was quite disconcerting, however I did manage a level of success, and went home with eleven portraits to work with.

I carried out the shoot on a reasonably bright day, relying mainly on natural light and using fill flash where necessary. As the weather was favorable, a number of the shopkeepers suggested that I take their photograph outside and include their shop. I had already considered and disregarded this prior to the shoot. I believed that shooting the subject at full or half length outside to include the premise might reduce the significance and indeed impact of the subject. This might also rendering the portrait static and formal, not unlike the photographs of competition winners seen in local and community newspapers. Including background and props was essential in strengthening the context of my series, so the most obvious option was to shoot the interior. August Sander’s, Pastrycook 1928, was a reference point for my portraits, although I desired a more candid feel, similar to his Young Farmers.

Bernd and Hilla Becher photographed their typologies from the same angle, and at approximately the same distances. In the interest of consistency, I maintained the same focal length across the series by using my Fujifilm x100s with 23mm fixed lens (35mm equivalent), and like the Bechers, I, for the most part framed my subjects to occupy similar proportion of the frame. Sufficient fore and background detail was included using a medium depth of field (f8).

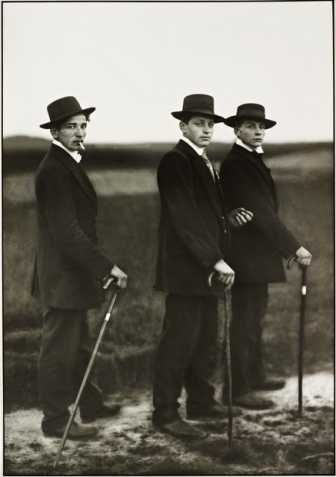

I turned to Joel Sternfeld’s Stranger Passing for inspiration on how best to achieve a sense of interruption in my subjects. Although many of sternfeld’s subjects are capture at full length and include background and props, it isn’t always clear as to what action or activity he has interrupted. ‘Using August Sander’s classic photograph of three peasants on their way to a dance as a starting point, Sternfeld employed a conceptual strategy that amounts to a new theory of the portrait, which might be termed “The Circumstantial Portrait”.’ (Nickels). The blurb from Stranger Passing presents a number of questions that one might consider when viewing the work. ‘What happens when we encounter the other in the mist of a circumstance? What presumptions, if any, are valid?’ (Steidl). While my intention isn’t to go as far as challenge viewer’s presumption about the subject. From reviewing Sternfeld’s work I did decide that I could best achieve a sense of interruption by posing the subjects behind the protection of their counters, where possible, which I feel that it put most of the subjects at ease.

The First Edit

After deleting obvious flawed images, I printed contact sheets and physically mark or annotated them. I find that this makes the editing process a much simpler affair, allowing for increased clarity and justification on edit decision making. I added this to my workflow during the Context and Narrative module, and have done it ever since. Below I’ve included a number of annotated contact sheets.

My editing process resulted in the following 11 portrait.

I viewed all of the above image in both colour and black and white. While I like some of the black and white conversions, I found the subjects were beginning to blend into their busy and detailed surroundings. Black and white could possibly have been a stronger option if I had shot the portraits using a shallower depth of field. It was a difficult decision. That aside, I do like the contemporary feel that colour gives this series and as Joel Sternfeld once said, ‘black and white is abstract, colour is not. Looking at a black and white photograph, you are already looking at a strange world. Colour is the real world.’

A number of the images immediately engage my interest and including them was a decision that I was biased towards. However, I had to create consistency across the series, and so I began to eliminate rather than select photographs. The subjects in image 6 and 7 seem a little disinterested, while those in 8 and 9 seem uncomfortable. Those 4 are all quite different and are in stark contrast to the other 7, where everyone has a smile and is engaging positively with the camera. In order to reduce my portraits to just five, I also cut image 5 and 11. While I like both images, I feel that the subject in image 5 is not as sharp as I would like, while in image 11, the subject’s pose is inconsistent with the rest of the series. The final selection can be seen below

Assignment 1: The non-familiar

Reference

Ang, T. (2014) Photography The Definitive Visual History, London: Dorling Kindersley.

Artsy (2017) Artsy [online], available: https://www.artsy.net/search?q=sternfeld [accessed 29 Nov 2017].

Badger, G. (2007) The Genius of Photography: How photography has changed our lives, London: Quadrille.

Beth (2012) ‘Photographic Typologies: The Study of Types’, Redbubble Blog [online], 26 Apr, available: https://blog.redbubble.com/2012/04/photographic-typologies-the-study-of-types/ [accessed 29 Nov 2017].

Bright, S. (2010) Auto Focus: the Self Portrait in Contemporary Photography, London: Thames and Hudson.

Buchmann Gallerie (2017) Buchmann Galerie [online], available: http://www.buchmanngalerie.com/current [accessed 29 Nov 2017].

Clarke, G. (1997) The Photograph, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Cotton, C. (2009) the photograph as contemporary art, new ed. London: Thames & Hudson.

Jeffrey, I. (2010) Photography A Concise History, London: Thames & Hudson Ltd.

Kim, E. (2017) Eric Kim Photography: 6 Lessons Joel Sternfeld has Taught Me about Street Photography [online], avalable: http://erickimphotography.com/blog/2014/02/14/6-lessons-joel-sternfeld-has-taught-me-about-street-photography/ [accessed 29 Nov 2017].

Luhring Augustine (2017) Luhring Augustine [online], available: http://www.luhringaugustine.com/artists/joel-sternfeld/bio [accessed 29 Nov 2017].

MoMA (2017) August Sander [online], available: https://www.moma.org/artists/5145 [accessed 29 Nov 2017].

San Fransisco MoMA (2017) SFMoMA [online], available: https://www.sfmoma.org/search/?q=sternfeld&page=1 [accessed 29 Nov 2017].

Sternfeld, J.(2001) Stranger Passing, New York: Bulfinch.

Tate (2016) Tate [online], available: http://www.tate.org.uk/art/search?q=August%20sander [accessed 29 Nov 2017].

Warner Marien, M. (2010) Photography: A Cultural History, 3rd ed., London: Laurence King.